Fecal incontinence in adults

Fecal incontinence has a significant social and economic impact and significantly impairs quality of life. Fecal incontinence can contribute to the loss of the ability to live independently. This topic will review the etiology and evaluation of fecal incontinence in adults. Our recommendations are largely consistent with guidelines issued by the American College of Gastroenterology. The management of fecal incontinence in adults is discussed in detail, separately.

Risk factors — Risk factors for FI include:

Hormone therapy is associated with an increased risk of FI among postmenopausal women. In a study of over 55,000 women participating in the Nurses' Health Study, the risk of developing FI was increased in both past and current users of hormone therapy (hazard ratio [HR] 1.3, 95% CI 1.2-1.3 and HR 1.3, 95% CI 1.2-1.5, respectively).

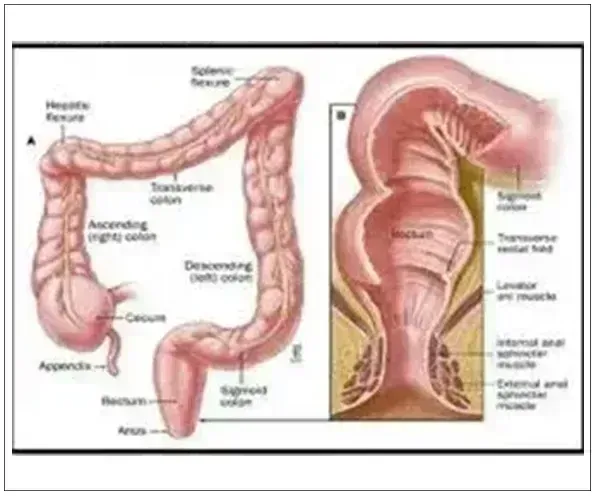

The processes involved in normal defecation are complex, involving a sequence of events that are initiated by the entry of stool into the rectum. Progressive rectal distension leads to reflex relaxation of the internal anal sphincter. The urge to defecate increases as stool continues to enter the rectum from the sigmoid colon.

When defecation is desired, the anorectal angle is voluntarily straightened (which is facilitated by squatting or sitting), and abdominal pressure is increased by straining. This results in descent of the pelvic floor, contraction of the rectum, and inhibition of the external anal sphincter, thereby evacuating the rectal contents.

Continence depends upon a number of factors including cognitive function, stool volume and consistency, colonic transit, rectal distensibility, anal sphincter function, anorectal sensation, and anorectal reflexes. Within the anorectum, anatomic barriers that help preserve continence include the rectum, the internal anal sphincter, external anal sphincter, and puborectalis muscle.

Loss of continence can result from dysfunction of the anal sphincters, abnormal rectal compliance, decreased rectal sensation, altered stool consistency, or a combination of any of these abnormalities. Incontinence is usually multifactorial, since these derangements often coexist. Mild impairment of any one mechanism will usually not cause incontinence, since the other mechanisms for maintaining continence can usually compensate. Patients with urge incontinence often have weakness of the external anal sphincter as well as decreased rectal capacity and rectal hypersensitivity, and patients with passive fecal incontinence often have weakness of the internal anal sphincter. Some of the more common causes of incontinence will be discussed below.

Anal sphincter weakness — Anal sphincter weakness may be due to traumatic or atraumatic causes. Atraumatic causes of anal sphincter weakness include neurologic disorders such as diabetes or spinal cord injury, or infiltrative disorders (eg, systemic sclerosis). Decreased anal sphincter pressures can result from anal trauma, such as after childbirth or surgery on the anal sphincter or surrounding structures (eg, anal fistulas, hemorrhoids, or uncommonly after injection of botulinum toxin for anal fissures).

Anal sphincter laceration or trauma to the pudendal nerve during vaginal delivery may result in fecal incontinence. Fecal incontinence may occur immediately or many years after delivery. Risk factors for fecal incontinence after vaginal delivery include the use of forceps, a high-birth weight infant, a long second stage of labor, and occipitoposterior presentation of the fetus. However, all anal sphincter tears do not result in fecal incontinence. A systematic review that included more than 100 patients who underwent endoanal ultrasonography after vaginal delivery estimated that anal sphincter defects were detectable in 27 percent of primiparous women, but only 29 percent of women with an anal sphincter defect were symptomatic. In a population-based study, rectal urgency, rather than obstetrical sphincter injury, appeared to be the main risk factor for fecal incontinence in women.

Decreased perception of rectal sensation — A number of conditions are associated with impaired rectal sensation including diabetes mellitus, multiple sclerosis, dementia, meningomyelocele, and spinal cord injuries. Patients with diabetes mellitus can have reduced internal anal sphincter resting pressure, which may result in incontinence. Diarrhea secondary to autonomic neuropathy may also contribute to fecal incontinence in these patients.

Decreased rectal compliance — Decreased rectal compliance leads to increased frequency and urgency of bowel movements because the ability of the rectum to store fecal matter is reduced. This can lead to fecal incontinence even if sphincter function is normal. Disorders associated with decreased rectal compliance include ulcerative proctitis, radiation proctitis, and proctectomy.

Overflow — Fecal retention and fecal impaction are common causes of fecal incontinence in older adults. Hard stool results in fecal impaction that produces constant inhibition of internal anal sphincter tone, permitting leakage of liquid stool around the impaction. A number of factors may contribute to the development of fecal impaction in older adults including impaired cognitive function, immobility, rectal hyposensitivity, and inadequate intake of fluids.

Idiopathic — Idiopathic fecal incontinence occurs most commonly in middle-aged or older women. Although by definition, the cause cannot be identified, it is probably due to denervation of pelvic floor muscles resulting from stretch injury to pudendal and sacral nerves as might occur following a prolonged vaginal delivery or defecatory straining and is often associated with disorders of the anal sphincters/puborectalis, rectal capacity or sensation.

Evaluation of patients with fecal incontinence begins with a history, physical examination, and endoscopic evaluation. In patients who fail to respond to initial management, we perform additional testing to detect functional and structural abnormalities of the anal sphincters, the rectal wall, and the puborectalis muscle and provide a better understanding of the underlying pathophysiology that is needed to guide management.